Floodwaters in the Philippines do not only carry rain and destruction – they also carry a devastating revelation: our flood defenses are corrupted. Revelations of collusion between public officials and private contractors, especially involving St. Gerrard Construction owner Cezarah “Sarah” Discaya, show how safeguards have become betrayals.

We have seen the aftermath: homes lost, crops ruined, communities shattered – despite massive government spending on flood control. The vulnerability we face is not due to nature’s force, but because of broken governance.

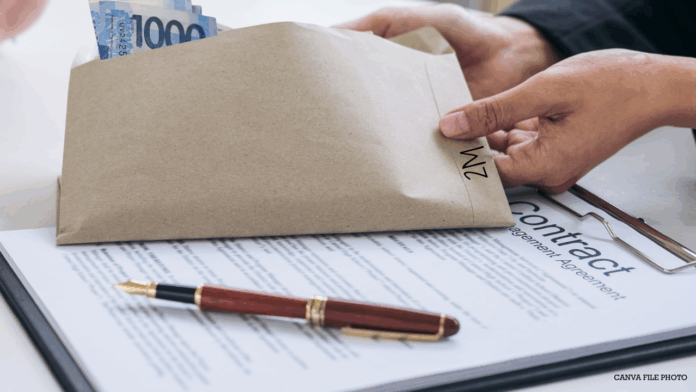

Allegations linking Discaya and her husband through firms like St. Gerrard Construction, Alpha & Omega, St. Timothy Construction, Elite General Contractor, and several others suggest that millions that were meant for dikes, drainage, and barriers vanished into kickbacks and inflated contracts. These Discaya-linked projects, especially in Bulacan and Iloilo City, have been flagged as substandard, malfunctioning, or “ghost” projects that failed to serve their purpose.

But they are only part of a larger, more troubling web.

Other major contractors have also cornered flood-control funds. The Co family of Bicol, notably Sunwest, Inc. and Hi-Tone Construction & Development Corp., has secured billions in contracts, tied to Congressman Zaldy Co and his relatives. Also, a select group of 15 contractors, including Alpha & Omega, St. Timothy, Legacy Construction Corp., Sunwest, Hi-Tone, QM Builders, EGB Construction, Wawao Builders, MG Samidan Construction, Triple 8 Construction & Supply, Centerways Construction, Topnotch Catalyst Builders, Royal Crown Monarch Construction, L.R. Tiqui Builders, and Road Edge Trading & Development, collectively cornered about 20 percent of the flood-control budget, or roughly ₱100 billion.

When an official rubber-stamps a fake project, they are not approving a faulty structure; they are sealing the fate of future flood victims. When contractors skimp on quality for profit, they are not saving resources; they are risking lives. Billions meant to protect communities instead funded lavish lifestyles, while ordinary Filipinos face storms unshielded.

The physical wreckage of a flood can be cleaned up, but the emotional and mental toll is far harder to heal. How can people trust a system that, time and again, betrays them at their most desperate hour? This isn’t just about money; it’s about a complete breakdown of trust. It’s about a nation that feels utterly abandoned by its leaders, left to fend for itself against both the forces of nature and the forces of greed.

The connection is painfully clear: the corruption in the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) and the failure of flood control projects are not separate issues from the human suffering we see on the news. They are one and the same. Until those responsible are held accountable, from the highest halls of power to the contractors on the ground, every flood will not only wash away homes but also erode our faith in the possibility of a just and safe future.