In previous installments of the Maniobra Series, we dissected the intricate dance of political blocs, appointments, and the covert dealings that shape governance.

Now, we turn to the currency of transactional politics: contracts.

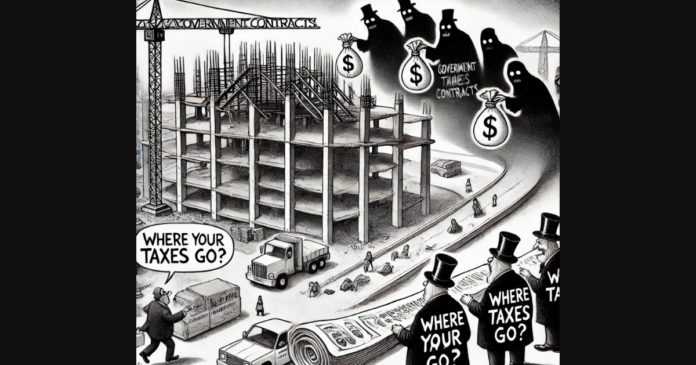

As everyone knows, the government spends billions each year on contracts. These don’t necessarily have to be big-ticket projects like bridges, dams, roads, or buildings. Contracts for services, venue rentals, catering, equipment leasing—even paper, tarpaulins, and ballpens—can be used to pay off political favors.

Behind these transactions is an entire bureaucratic system called procurement. For the technically inclined, it is governed by Republic Act 9184, or the Government Procurement Reform Act, along with its implementing rules and audit guidelines.

But for our purposes here, what matters is this: contracts are often used not just to procure services, but to reward loyalty.

Suppliers and contractors who backed a candidate during their campaign bids are often repaid with a slew of government projects. Bidding rules still apply, but these “supporters” gain first dibs to bid documents, and insider information, among others. For those in the know, early access, especially over bid evaluations, can tilt the playing field.

Some don’t win because they are the most qualified; they win because they are politically connected.

It’s not just private companies. Contracts can also be awarded to groups labeled as “partners” or “co-implementors” of government programs—or as direct beneficiaries. This brings us back to one of the country’s largest corruption scandals: the PDAF scam.

The Priority Development Assistance Fund (PDAF)—commonly known as the pork barrel—was originally intended to support local development projects, but later became a tool for political payoffs. Standing front and center of this scandal was Janet Lim-Napoles, the businesswoman who redirected public funds through fake non-governmental organizations (NGOs).

The result? Lawmakers endorsed projects, NGOs linked to Napoles received the funds, and payoffs flowed back to officials. The pork barrel scam resulted in an estimated loss of ₱10 billion, implicating several high-ranking leaders from both elected and appointed positions.

Some of these officials continue to hold influential roles today.

Beyond the financial loss, the scandal severely damaged the credibility of legitimate NGOs and civil society organizations, many of which still face public distrust and stricter accreditation requirements to this day.

Now, one might ask: what’s so bad about having preferences in bidders or contractors? Simply put, it leads to stagnation. When government contracts are circulated only among a select few, it breeds monopolies, stifles competition, and discourages innovation.

Instead of rewarding capability or cost-efficiency, contracts are awarded based on proximity to power. Over time, this creates a closed ecosystem where services deteriorate, pricing inflates, and development slows down—all while taxpayers foot the bill.

It’s us paying for the services and gifts provided to only a very select few.

Think of it like going to the same overpriced store over and over, just because the owner is friends with the one holding the purse: no comparison, no better options, no questions asked. And we’re the ones paying the receipt.

So, the next time you see a tarp that says “This is where your taxes go”, ask yourself: who really benefited—and who just got paid?